Welcome to an in-depth guide on running nutrition, the cornerstone of athletic performance, recovery, and injury prevention for runners of all levels. Whether you’re aiming to complete your first 5K, smash a personal best in a half-marathon, or conquer the 26.2 miles of a full marathon, what you eat is just as crucial as your training plan. This comprehensive article delves into the science and practical application of fueling your runs, covering everything from daily macro intake to race-day strategies and essential supplements.

The Runner’s Plate – Why Nutrition Matters

For a runner, food is more than just sustenance; it’s fuel, building material, and medicine. Proper nutrition dictates your energy levels, the efficiency of your muscle repair post-workout, and your body’s ability to adapt to training stress. A balanced diet prevents the energy-sapping fatigue often experienced during long runs and speeds up recovery, allowing you to consistently perform at your best. Ignoring the nutritional component of your training can lead to poor performance, fatigue, the “bonk” (hitting the wall), and increased risk of stress fractures and illness. This guide will provide the expert framework you need to construct a winning dietary strategy tailored to the demands of distance running.

The Daily Foundation: Macronutrients for Runners

A runner’s diet must be carefully balanced, with specific attention paid to the three major macronutrients: carbohydrates, protein, and fats. The ideal ratio can vary depending on your training volume, intensity, and individual metabolism, but general guidelines serve as an excellent starting point.

Carbohydrates: The Primary Fuel Source

Carbohydrates are the most critical macronutrient for runners. They are broken down into glucose, which is stored in the muscles and liver as glycogen. Glycogen is the primary fuel source for moderate-to-high-intensity exercise, including most running efforts. When your glycogen stores are depleted, your performance suffers drastically – this is the dreaded “bonk.”

Types and Timing of Carbohydrate Intake

- Complex Carbohydrates: These should form the bulk of your daily intake. They are digested slowly, providing a sustained release of energy.

- Examples: Whole grains (oats, brown rice, quinoa, whole wheat bread), sweet potatoes, legumes, and starchy vegetables.

- Simple Carbohydrates: While generally limited, they are crucial immediately before, during, and after high-intensity or prolonged exercise for rapid energy and glycogen replenishment.

- Examples: Fruits (bananas, berries), sports drinks, energy gels, and white rice/pasta (especially during the 24-48 hours leading up to a race).

A general recommendation for runners in moderate training is 5–7 grams of carbs per kilogram of body weight per day.

Protein: Repair and Recovery

Protein is essential for muscle repair, recovery, and synthesis. Running, especially long-distance and speed work, causes micro-tears in muscle fibers. Protein provides the amino acids needed to rebuild and strengthen these tissues, which is key to improving stamina and preventing overuse injuries.

Quality and Quantity of Protein

- Sources: Focus on lean, high-quality sources, including poultry, fish, eggs, dairy (Greek yogurt, cottage cheese), legumes, tofu, and lean cuts of beef.

- Intake: Most running nutrition experts recommend $1.2–1.7$ of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for endurance athletes. Spreading protein intake across all meals and snacks, including a dose post-run, optimizes muscle protein synthesis. Aim for $20–30$ grams of protein within the first hour after a hard workout.

Fats: Energy Reserves and Essential Functions

Dietary fats are a necessary energy reserve, particularly for low-intensity, long-duration running where the body relies more heavily on fat oxidation for fuel (fat burning). They are also vital for hormone production, vitamin absorption (vitamins A, D, E, and K), and general cell health.

- Healthy Fats: Prioritize unsaturated fats, especially monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

- Examples: Avocados, nuts, seeds, olive oil, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel) rich in Omega-3 fatty acids, which have potent anti-inflammatory properties crucial for recovery.

- Limit: Minimize intake of trans fats and limit saturated fats, as they offer little nutritional benefit for performance and can impact cardiovascular health.

Fats should generally constitute $20–30$ of your total daily caloric intake.

Hydration: The Unsung Hero of Performance

Hydration is perhaps the most overlooked element of running nutrition, yet even mild dehydration can significantly impair performance, increase perceived exertion, and raise core body temperature. Fluid intake is crucial before, during, and after every run.

Electrolytes and Fluid Balance

Water alone is often insufficient, especially during long or hot runs. Electrolytes (sodium, potassium, magnesium, and chloride) are lost through sweat and must be replaced to maintain fluid balance, nerve signaling, and muscle function.

- Pre-Run: Drink $16–20$ ounces of water or a sports drink 2–3 hours before your run, and $7–10$ ounces 20 minutes before starting.

- During Run: Aim for $7–10$ ounces of fluid every $15–20$ minutes. For runs lasting over 60–90 minutes, a sports drink containing carbohydrates ($30–60$ grams per hour) and electrolytes is highly recommended.

- Post-Run: Replenish fluids at a rate of $1.5$ times the estimated fluid loss (measured by weight change) to ensure full recovery.

Timing is Everything: Pre-, During, and Post-Run Fueling

The timing of your nutrient intake, often called nutrient timing, is just as important as the quantity and quality of the food itself. Strategic fueling maximizes energy availability and accelerates recovery.

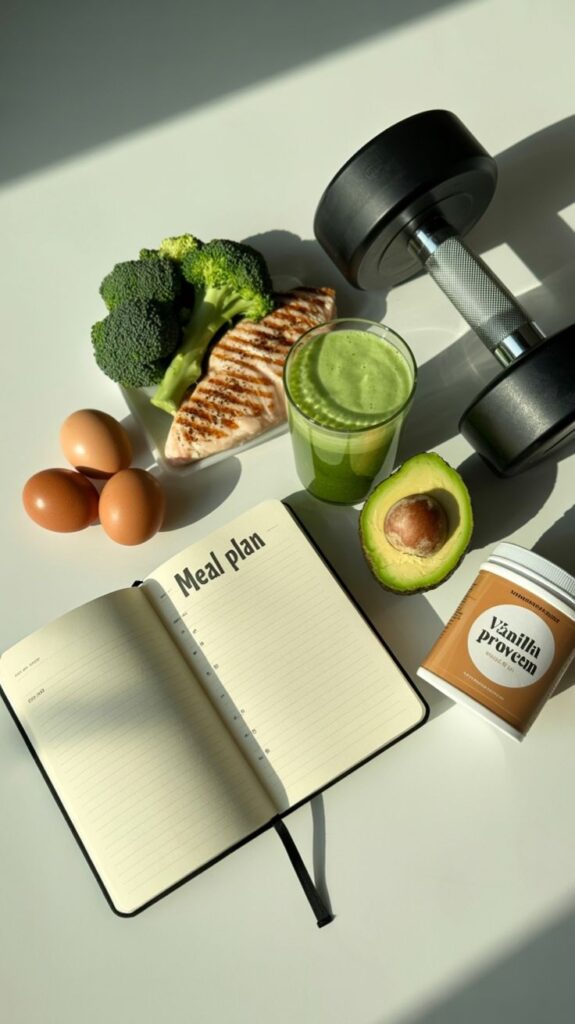

Pre-Run Meal: Top Off the Tank

The goal of the pre-run meal is to top up liver glycogen stores and settle your stomach.

- 3–4 Hours Before: A larger meal focused on complex carbohydrates, moderate protein, and low fiber/fat.

- Example: Oatmeal with banana and a scoop of protein powder, or a bagel with peanut butter and a glass of juice.

- 30–60 Minutes Before: A small, easy-to-digest snack, predominantly simple carbs.

- Example: A small banana, a few dates, or a handful of pretzels.

Crucial Note: Always test your pre-run meals and snacks extensively during training, never on race day, to ensure they don’t cause gastrointestinal distress.

Fueling During the Run: Maintaining Energy

For runs exceeding 60–90 minutes, consuming carbohydrates during the run prevents glycogen depletion.

- Goal: $30–60$ grams of carbohydrates per hour. Highly trained athletes may benefit from up to $90$ grams per hour using multiple carbohydrate types (glucose/fructose blend).

- Sources: Energy gels, chews, sports drinks, and sometimes simple foods like pretzels or dried fruit. Start consuming fuel early, typically around the 45-minute mark, and continue every 30–45 minutes thereafter.

Post-Run Recovery: The Golden Window

The $30–60$ minute period immediately following a run is the “glycogen window” or “golden hour,” when muscle cells are most receptive to absorbing nutrients for repair and replenishment.

- Ideal Ratio: A $3:1$ or $4:1$ ratio of carbohydrates to protein.

- Example: A recovery smoothie with fruit, milk/yogurt, and protein powder; or chocolate milk, which naturally offers this ratio.

- Function: Carbohydrates rapidly restore depleted glycogen, and protein provides the amino acids necessary for muscle repair.

Race Day and Tapering Nutrition

Race day success begins with the taper, the period of reduced training volume leading up to the event. Tapering nutrition focuses on maximizing muscle glycogen stores—a process called carbohydrate loading.

Carbohydrate Loading: Maximizing Glycogen

True carbo-loading doesn’t involve dramatically increasing your calorie intake; it means increasing the percentage of calories that come from carbohydrates while slightly reducing fat and protein.

- When: Start 3 days before the race.

- How: Aim for $8–12$ of carbohydrates per day.

- Focus: Easy-to-digest, low-fiber sources to prevent GI issues on race day: white rice, pasta, potatoes (skin removed), bananas, and plain breads.

- Avoid: High-fiber foods, excess fat, and foods that may cause gas or bloating.

Race Morning Protocol

The goal is a familiar, high-carb, low-fiber, low-fat meal 3–4 hours before the starting gun.

- Examples: Plain bagel, white toast with jam, oatmeal (not steel-cut), rice cakes, or a sports energy bar you’ve tested many times.

- Hydration: Sip on water or an electrolyte drink. Stop drinking about 45 minutes before the start to allow for one last bathroom trip.

During the Race

Execute the fueling strategy you perfected during your long training runs. Use familiar gels/chews, stick to the aid station drinks you practiced with, and maintain consistent hydration.

Supplements and Special Considerations

While a balanced diet should cover most nutritional needs, certain supplements and dietary adjustments can be beneficial for runners.

Essential Micronutrients

- Iron: Crucial for oxygen transport (hemoglobin). Runners, especially women and vegetarians, are at risk for deficiency, which leads to fatigue and poor performance. Consult a doctor before supplementing.

- Vitamin D: Important for bone health, immune function, and muscle function. Many people, particularly those living in northern latitudes, are deficient.

- Calcium: Essential for bone density and muscle contraction, particularly important for preventing stress fractures.

Performance-Enhancing Supplements (Ergogenic Aids)

- Caffeine: A widely used, legal ergogenic aid shown to enhance endurance and reduce the perception of effort. Take $3–6$ about an hour before a race.

- Creatine: While traditionally associated with strength sports, it can help endurance athletes by enhancing muscle glycogen storage, reducing muscle damage, and improving high-intensity sprint bursts.

- Beta-Alanine: A precursor to carnosine, which helps buffer acid in the muscles, potentially benefiting performance in short, high-intensity efforts (e.g., the final kick of a race).

Vegetarian, Vegan, and Specialty Diets

Runners following plant-based diets must be meticulous in monitoring their intake of Vitamin B12, Iron, Zinc, and Omega-3s, which are abundant in meat and fish. Strategic use of supplements and fortified foods (e.g., fortified plant milks) is often necessary to prevent deficiencies that impact running performance and health.

Conclusion: Fueling Your Running Success

Optimal running nutrition is an ongoing, personalized process that evolves with your training volume, goals, and experience. By prioritizing complex carbohydrates as your primary fuel, ensuring adequate protein for muscle repair, and maintaining meticulous hydration and electrolyte balance, you provide your body with the resources it needs to adapt, recover, and excel. Remember to test, practice, and refine your fueling strategy during training so that on race day, your nutrition is the foundation of your success, not a factor that holds you back. Consistency in your daily diet is the ultimate performance-enhancing secret.

No problem at all! Here is the FAQ section translated and presented in English, following the previous structure and guidelines.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions on Running Nutrition

1. What is “hitting the wall” (bonk) and how can I avoid it?

“Hitting the wall,” or “bonking,” is a sudden, severe feeling of fatigue and inability to continue running, caused by the near-complete depletion of glycogen stores in the muscles and liver. You can avoid it by thoroughly conducting a “carbohydrate load” before a long race and consistently consuming carbohydrates (sports gels, drinks) during the run, starting at the 45–60 minute mark, aiming for $30–60$ grams per hour.

2. How much fluid should I drink during a long run?

It is recommended to drink $7–10$ ounces (about $200–300$ ml) of fluid every $15–20$ minutes. For runs lasting more than 60–90 minutes, you should use drinks containing electrolytes and carbohydrates to replace the sodium and glucose lost through sweat.

3. What is the ideal snack before a morning run?

The ideal snack is a light, fast-digesting food high in simple carbohydrates and low in fat and fiber, consumed $30–60$ minutes before the start. Excellent options include: half a banana, a few dates, a handful of raisins, or a small slice of white toast with jam.

4. Should I drink a protein shake after training?

Yes, it is very beneficial. Consuming $20–30$ grams of protein combined with carbohydrates (an ideal ratio of $3:1$ or $4:1$ carbs to protein) within $30–60$ minutes after an intense workout helps rapidly repair muscle tissue and replenish glycogen stores.

5. Does caffeine help improve running performance?

Yes, caffeine is an effective ergogenic aid that can enhance endurance, reduce the perception of effort, and improve focus. The recommended dose is $3–6$ mg per kilogram of body weight one hour before the start of a long run or race.

6. Do I need to take vitamins and minerals?

For most runners with a well-balanced diet, additional vitamins are not necessary. However, women, vegans, and high-mileage runners may be at risk for deficiencies in Iron, Vitamin D, and Calcium. Always consult a doctor before starting any supplements.

7. What is “carbohydrate loading” and when should I do it?

Carbohydrate loading is a dietary strategy aimed at maximizing muscle glycogen accumulation before endurance events (half-marathon, marathon). It should be started $3$ days before the race, increasing carbohydrate intake to $8–12$ grams per kilogram of body weight per day, while simultaneously reducing fiber intake.

8. Is it okay to run fasted?

Short, easy runs (under 60 minutes) performed in a fasted state may be acceptable and even beneficial for improving the body’s ability to use fat as fuel. However, long or high-intensity workouts should always be performed after adequate carbohydrate intake to prevent performance degradation and muscle breakdown (catabolism).

9. How does nutrition help prevent injuries?

A diet rich in protein for muscle repair, calcium and Vitamin D for bone health, and Omega-3 fatty acids to reduce inflammation plays a key role in preventing injuries like stress fractures and tendinitis.